The Grand Canyon, Rim-to-Rim. 21-ish miles, 5000 feet down from the South Rim then another 6,000 up the North; that’s more than a vertical mile. If you’re like most people, you’ll only realize what that means when you’re at the bottom looking back up.

So the first piece of advice I have for you: Don’t try this in July. It’s like a convection oven down there, and you’re the thing they put in to bake. And the second piece of advice: No matter what month you hike — take plenty of time and plenty of water.

In Your Bucket Because…

- This is, quite simply, one of the planet’s unique landscapes.

- To see the Grand Canyon on foot is to more intensely experience its views, geography, and geology slowly: One layer at a time, step by step.

- Good for fit hikers, photo buffs, and geology buffs. Families with hardy teens would enjoy this if the kids are well-prepared.

I was hiking Grand Canyon as part of a larger hike of the 750-ish-mile-long Arizona Trail. The Arizona Trail runs from the Mexican border to Utah, and somewhere, it has to cross the Colorado River, which it does using the Grand Canyon “corridor trails,” so named because they act as the major north-south corridors across the canyon. They are also the trails tourists are most familiar with. The South Kaibab and the Bright Angel trails both depart from the South Rim and descend all the way to the Grand Canyon’s floor. The North Kaibab Trail descends to the floor from the North Rim. The trails meet at the bottom near Bright Angel Campground and Phantom Ranch, which is where most everyone camps.

Rangers recommend the corridor trails to first time Grand Canyon visitors because these paths are wide, with relatively gentle switchbacks. (In fact, the corridor trails are used by mule trips into the Grand Canyon.) They are well-maintained and are regularly patrolled by rangers. The downside is that it can be difficult to get a permit to camp along them, but here’s a secret: There are generally a few no-shows, and those permits are handed out first come first serve. If you didn’t manage to book a permit in advance, get to the ranger station early, listen to the lecture (“Bring water. Bring water. Bring water”), and you might get lucky and score a spot.

Walking Through Geology

Some facts: The oldest rock layer that underlies the Grand Canyon is up to two billion years old. Even the younger layers are ancient — some 600 million years — which means that some of the rocks you are walking on when you reach the canyon floor predate rats and sharks and dinosaurs and cockroaches and pine trees and cactus and even the most basic multi-cellular life, not to mention people. There are some 40 distinct layers in the 277-mile-long canyon, and what you notice most are the changing colors: beiges, a sulfury yellow, light and dark oranges, burnished reds like the colors of Italian tiles, and deep purples. Plus, there’s a sort of greenish looking flat layer called the Tonto, although some of its color is due to the scruffy vegetation that insists this is an appropriate place to set up house.

What I kept wondering, though, was what it would have been like to be the first European to see this place: From the south, the land is flat and forested and entirely unremarkable, and then BAM! a hole opens up in the earth and you could put all of Manhattan Island inside and it would barely take up any space at all. How would you respond to that if you had no idea it was coming?

It’s crowded for the first few miles down: We’re passed by mule trains, the riders looking terrified and thrilled at the same time. But soon, the dayhikers start to turn around and it’s just us backpackers. It’s quiet in the canyon. And hot. The air shimmers. Our water bottles look suddenly very meagre.

Hiking Rim to Rim

The night before we hiked, we’d stayed with friends who worked at the Canyon, she a nurse, he a ranger. They’d told us about the rescues they do. A lot of people die here — there’s a whole book about nothing but Grand Canyon fatalities — and a lot of the deaths are caused by falls, lack of water, and heat. There’s an insidious condition called hyponatremia, where your body is so depleted of both water and electrolytes that it can’t even hold water, and your kidneys fail and if you don’t get help you die. So about the water? Listen to the rangers.

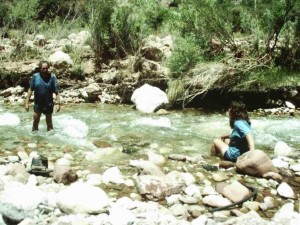

Oh, and another thing: The Colorado River water isn’t great drinking water: it’s polluted from all the rafters, and it’s silty, so it’s hard to filter. There’s plenty of water at the campground, and you can even buy a beer at the canteen, if you let yourself forget that alcohol contributes to dehydration.

We camped in our assigned spots, where we learned that we didn’t have to worry so much about rattlesnakes and tarantulas as we did about deer that liked to chew on salty T-shirts and could get aggressive. Apparently, an annoyed Bambi can pack a punch, and people occasionally get hurt. But no Bambis invaded our peace that night. I suspect it was too hot.

Our the next day’s destination was the North Rim: It’s 14 miles straight up, so we broke it up at a campsite about midway, making this a three-day, two-night trip. The North Rim is nice: It gets fewer visitors, so the trails are less crowded. It’s got a whole different feel: windier and more forested toward the top. Most people who hike down the South Kaibab go back up the Bright Angel and return to the South Rim because they’ve got the “how do I get back to my car?” problem. Being on foot, I didn’t have to worry about that until Utah.

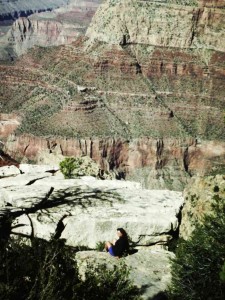

On the corridor trails, you’re never far from other people, but if you step off to explore a little, it can feel that you’ve walked off the edge of the earth. In a way, I guess you have. I found myself wondering if perhaps I could be standing somewhere no one had ever been before. I know how unlikely it was, especially near the main corridors, but it didn’t stop the feeling of utter aloneness, and discovery, and peace.

Practicalities: Safety for First-Time Hikers

- Don’t attempt to go to the bottom of the Grand Canyon and back up in one day. People have (literally) died trying to do this.

- Bring more water than you think you need — at least one quart for every hour of planned hiking time. (Some people may need more.)

- Allow twice as much time for coming up as it took to go down. And twice as much water.

- Wear reasonable footwear: Athletic shoes are fine. Flip flops are not.

- Bring a blister kit. The heat of the Grand Canyon means people sweat more than normal, which leads to blisters.

- Bring clothing that provides protection against the sun, as well as plenty of sunscreen.

- Bring some easy-to eat snacks like GORP (a mixture of nuts, raisins, seeds, and sweets).

- Mule trains have the right of way. Move off the trail as directed by the pack-train leader.

This article is updated from a story that first appeared in 2012.