“So, you’ll be tramping on the Milford Track next, then?” said the friendly clerk. We were checking out of a hotel on the sunny northern tip of the South Island with its Mediterranean climate. Next on the itinerary: the southern mountains and some of the wettest land on earth.

“Well, I do hope it rains for you,” said our well-wisher.

And here I’d been thinking New Zealanders were so nice.

“You’ll see when you get there,” she said by way of explanation.

In Your Bucket Because…

- Are your really going to say “no” to a trek that has held the title of “finest walk in the world” for more than 100 years?

- This 33-mile trek is packed with scenery: Waterfalls, glaciers, rainbows, and rainforest.

- Good for adventurers, families, and photo buffs with waterproof cameras.

A Hiker, an Editor, and a Name that Stuck

Writers don’t usually get to title their own newspaper articles — something that has been going on for a quite a long time, if the 1908 experience of Kiwi poet Blanche Baugham is anything to go by. She turned in an essay titled, “A Notable Walk” to the London Spectator. An editor with an ear for the hook turned it into “The Finest Walk in the World.” The Milford Track has been called that ever since.

Having done a whole lot of other hikes that frequently show up on “best of lists,” I was curious to experience the trek that seemingly owned the title.

There are two ways to “tramp” (as it’s called in New Zealand) the Milford Track: The guided trip, where trampers have meals prepared for them and stay in plush huts, or the independent way — carry your own stuff, make your own meals, sleep in a communal hostel, find your own way. Only 90 permits are available each day, 50 allotted to guided hikers and 40 to independent trekkers. The cost differential is enormous, and the trek is both short enough and easy enough that trampers don’t need all that much help, so the independent permits sell out as soon as they are released. We’d managed to score one.

We arrived at Te Anau, the small Fyordland town near the start of the trek, on a rare sunny day. At the ranger station, we picked up our coveted permits and examined enormous yellow heavy-duty waterproof backpack liners that were prominently displayed for sale. The ranger scoffed (politely) at our pack covers, which he declared insufficient for the weather down here. As those pack covers had recently kept our gear pretty much dry through a solid month (27 days out of 30) of torrential rain in the North Cascades, it seemed to me that local pride might be overdoing the big bad rain thing. Still, the Milford Sound region of New Zealand’s South Island is one of the wettest places on earth, and if you truly are an experienced hiker, a stat like that should give you pause. So should the information that the trails here can flood to waist high. We bought the pack-liners.

“I Hope it Rains“

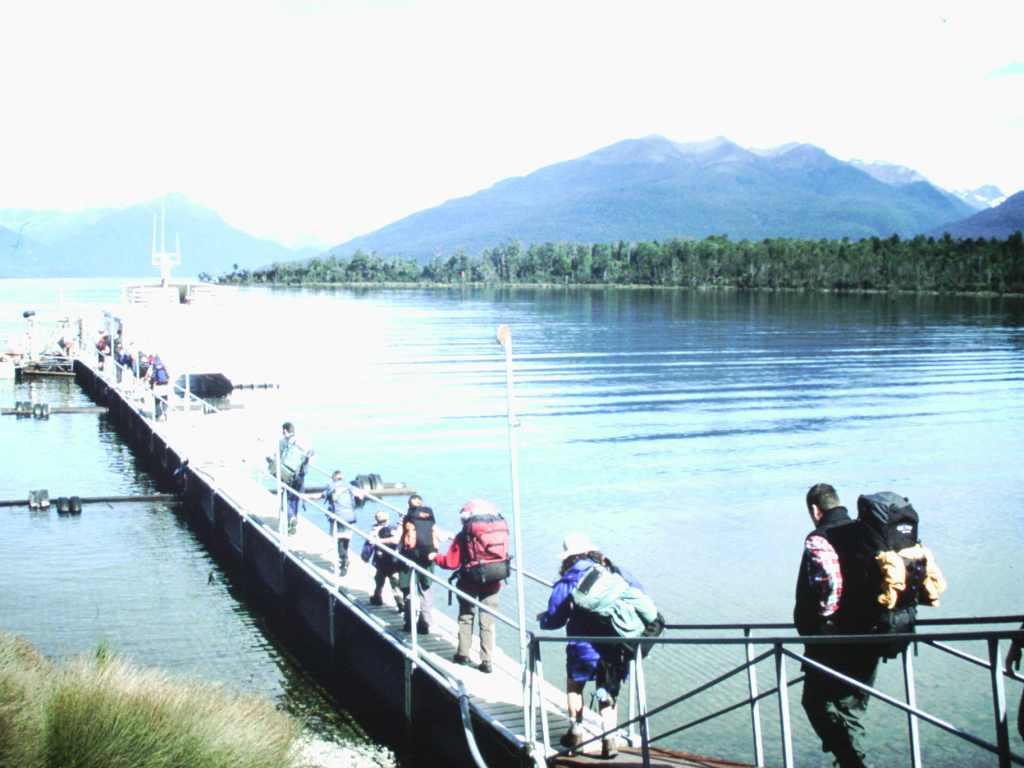

The trek begins with a boat ride across Lake Te Anau, the second largest fresh-water lake in New Zealand. Though it was mid-summer — meaning December — the high peaks were still capped by snow. The Milford Track is a three-night four-day hike, 53. 5 kilometers (33.2 miles) pretty much divided by going uphill through a steep-walled valley to Mackinnon Pass, then going downhill on the other side to end at Sandfly Point on Milford Sound. Independent and guided trampers depart on different boats and follow different schedules, so they never even meet. For independent trekkers, the first day is a short flat walk to Clinton Hut, which is nestled in a forest with some cliffs looming over head. Nice enough, but I wasn’t getting the “finest walk in the world” vibe.

The next day, our hotel clerk got her wish for us: Rain. Cats, dogs, buckets, sheets, and lashes. You don’t get to take a rain day on the Milford Track: 40 more people are just a day behind, permits in hand, waiting to take your place. We walked out and into it, into a steep-walled valley where we at once understood what the hotel clerk had said: This trek is all about rain. Hundreds of waterfalls plummeted down thousand-foot rock walls. The wind was so fierce that most of waterfalls only went halfway down; their waters ripped right from the rock by the wind, flung sideways over the valley floor. Where we were walking.

Nature has many faces: gentle and healing; whimsical, awe-inspiring. Think snowflakes, moonlit lakes, aardvarks, and Mt. Everest. This was nature in the guise of power: God in a temper tantrum, rain pelting horizontal, entire waterfalls, for crying out loud, blowing sideways. Weather like that puts you in your own encapsulated space. You can’t talk to your hiking partner because they can’t hear you, what with nylon hoods and pelting torrents and howling wind. You can’t stop. Taking pictures was out of the question, as I learned when I tried: my camera, protected in a Ziplock bag inside a plastic case, simply drowned. All you can really do is feel: The wind, the rain, the progress of your body, step by step, moving in regular motion, uphill, always up, your breath, your heart.

There are other things I can tell you about the Milford Track: The view from Mackinnon Pass is certainly up there in the “finest walk in the world” category, if that is, you get a chance to see it. We did, but only because while we were drying out at Mintaro hut, a short hike from the pass, the rain broke and the ranger insisted that we go up and take a look. “There’s no guarantee you’ll see anything there when you climb it tomorrow,” he told us, “Go now!” Wet clothes went back on, wet boots and wet socks on wet feet, and out we went onto wet trail to see the classic glaciated pass, with snow-covered peaks and hovering clouds creating their patchwork of light and shadow. The next day it was raining again.

On the other side of the pass, Sutherland Falls — at 1800 feet, New Zealand’s highest — are magnificent, although by the time we got there nearly 12 inches of rain had fallen in the preceding 24 hours and the water was pounding down, bouncing up, flying sideways, leaving us standing in an almost impenetrable mist. Even 50 yards away, we were getting soaked (or, more precisely, more soaked) by the errant spray.

That night we arrived at Dumpling Hut and the valley started to flood. All that rain from all those waterfalls needed somewhere to go. Where it went was on the trail. By morning, the water was, indeed, waist high. We weren’t going anywhere. Up and down the length of the track, hikers were stalled, waiting for water to recede and the rangers to give the all clear. Sometimes, we were told, if the trail was too flooded, helicopters are sent in: The hikers must stay on schedule. But this morning, all it took was time. By noon, the water had lowered to merely ankle-deep. We sloshed onward to Milford Sound, where a pre-arranged bus awaited our bedraggled group.

The Finest Walk in the World?

So, rain, cliffs, rain, waterfalls, rain, a spectacular mountain pass, rain; a really high, fierce, skin-soaking waterfall; rain, more cliffs, rain, more waterfalls, rain, a kea bird, rain, floods, cliff-lined Milford Sound. Also: good company in the huts, knowledgeable rangers, well-marked trail and a propitious break in the weather to let us see the trail’s scenic highlight.

What makes something finest walk in the world? Certainly scenery is part of the picture, but every mountain range has scenery. Unspoiled nature is certainly part of it, but there again, there’s a lot of competition. The Dr. Seuss forests on My. Kenya? The old growth cedars of the North Cascades? The enormous wildlands of Alaska’s Brook’s range? Is one finer than the other? What is this obsession we have with “best”? Is there even such a thing as “better than” when it comes to nature and mountains and forests? And how would Blanche Baughan and her editor have known, anyway? It’s not like they had walked all over the world.

There is no denying that the Milford Track packs in a mass of superlatives into its 33 miles: News Zealand’s second largest lake, its highest waterfall, certainly one of its most scenic pass. But there is also the quality of the experience, I think. Waist-high waters and waterfalls blowing sideways may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but in the more than 1000 days I have spent on hiking trails word-wide, I have to admit I’ve never had an experience quite like this one. And that’s what sticks with you, years later, when you are spinning your stories and mining your memories.

As the ferry carries me across Milford Sound, and I stand looking back at the mist-shrouded cliffs, I’m left to wonder if maybe Blanche got it right the first time, and it was the anonymous editor who got it wrong. Most accurately, The Milford Track was indeed what she called it: a notable walk.

Some months later a friend told me he was planning to hike the Milford Track. What did I think?

I smiled. “I hope it rains.”

Practicalities

It does not always rain as much as it did on us (12 inches in 24 hours), but this is a rainforest. Pack rain gear and waterproof bags for everything in your pack. In our case, a waterproof camera would not have been a stupid idea. For independent trampers, book as far ahead as possible. Bug repellent is a must: When the rain stops, the sandflies come out. (Maori myth has it that the gods invented sandlfies to keep people away from paradise.)

Originally published in 2012. Fact checked in 2020. No updating necessary. It still rains. Permits are still hard to get. They still call it the finest walk in the world.