The local usage is a model of English understatement. We are walking, not trekking, and these 2,000- and 3,000-foot tall bumps in the landscape are hills, not mountains. So I shouln’t have been surprised when the words “unmarked trail” and “a bit confusing” turned out to mean “completely obscured by mud and fog” and “total disorientation.”

Indeed, I am standing in the kind of fog that must have been the inspiration for the phrase “pea soup fog.” Underfoot, a muddy mess is laced by a cross-hatch of trails created by confused hikers who came before. The paths aren’t marked up here: Based on a few conversations with fellow walkers, I learn that there’s a consensus among the hardcore that England has very little wilderness, that wilderness should be wild, and that there should be some place left without copious trail signs from the “nanny state.” This is that place. Rainfall of more than 80 inches a year and steep trails through a surprisingly stark and raw landscape make this more of a challenge than you might think looking at the maps.

In Your Bucket Because…

- Walking across an entire country is pretty cool.

- This walk takes in some of England’s classic hill country scenery: moors, dales, hills, and striking cliff-framed seascapes on both ends.

- Good for hikers interested in history and a good meal at the end of a hard hiking day.

- The hike goes through three national parks: The Lake District, the Yorkshire Dales, and the North York Moors

The wind is flapping at my Goretex jacket, and it blows a hole in the misty curtain just long enough for me to see a giant, perhaps 10-foot tall, cairn that marks the summit of this mountain. From there, I pick up the trail again, and head downhill through the fog.

The Coast-to-Coast Route

The mountains here (I’m American; I get to use the word “mountain”) have the feel of much bigger peaks to me than their modest elevations would suggest, perhaps because of the lack of tree cover: It’s not a treeline issue, but rather the fact that much of the English landscape has long since been stripped of trees, harvested for shipbuilding, homes, railroads, and fuel centuries ago. The few “forests” that show up here on our map are pathetic little groves, survivors of an environmental disaster or newly planted fast-growing conifers (considered by some English environmentalists to be, if not another kind of environmental disaster, then at least an environmental mistake).

Northern England’s Coast-to-Coast route is a 192-mile footpath that passes near the narrowest part of England, from St. Bees on the Irish Sea to Robin Hood Pay on the North Sea. Pioneered by guidebook writer Bruce Wainwright, the Coast-to-Coast-doesn’t have status as an official long walk sanctioned by the government; official or not, it is one of England’s best known, most popular, and most scenic long-distance footpaths.

The Lake District

I picked up a pebble at the Irish Sea, my talisman for the journey, and started the walk along the cliffs. Soon, the path turns inland, and after a couple of gentle days complete with trail markers and signposts, it ascended into the mountains of the Lake District. We passed old Roman routes, detoured to Glasmere for a tour of Wordsworth’s home, and walked past lake landscapes now familiar to the world from Harry Potter movies. The Lake District is managed as a national park, but unlike the American definition, the English version of national parks encompasses farms, communities, historic sites, wildlands, and of course, the ubiquitous stone walls that march across the land, contour lines be damned.

The Yorkshire Dales

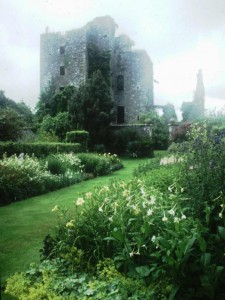

The middle third of the Coast-to-Coast Walk is characterized by history, high, bleak hills, and the contrasting lovely valleys of the Yorkshire Dales, protected as part of another national park. The village of Reeth is the center of park activity — there’s a small office and interpretive center where you can learn a little about the sheep industry that is traditional to the area. Next up is Richmond, only eleven miles away: You can use the balance of a short hiking day to visit its eleventh century castle. Or go back even farther in time: On Roman roads, you’ll follow in the footsteps of soldiers who marched here some two thousand years ago. Off in a field, even older standing stones circles a patch of earth for reasons still mysterious. And atop a hill known as Nine Standards, nine huge stone cairns guard the ridge, visible for miles. Who built them, and why? No one knows.

The North York Moors

The last third of the path begins with a rather flat — some would say monotonous — walk through farmlands. Then the path climbs into the Cleveland Hills, and enters the third national park on our route, the North York Moors. Think Wuthering Heights, and you’ll have a fair idea of what to expect in the next fifty miles. The wind-sheared high moors are exposed and harsh, but they have a stark and wild beauty.

For several miles here the Coast-to-Coast is contiguous with the Cleveland Way, one of England’s official long-distance walking paths. The route mostly winds through high heather moors, descending into towns, where you’ll pass an old toll road and one of England’s nineteenth-century steam train lines (still in service as a tourist attraction) before finally arriving for a grand finale along the rocky cliffs of the North Sea.

The path ends in picturesque Robin Hood’s Bay, where you can drop your Irish Sea pebble into the North Sea, and where a Coast-to-Coast guest book records the thoughts of hikers as they finish (or start) their journeys. My favorite came from a couple of Americans: “We’ve done yours. Now you come do ours.”

Practicalities

- I recommend carrying maps in addition to your cell phone. Being stuck in the fog with no battery is no joke. The Ordnance Survey has put together two strip maps of the trail at a scale of 1:25,000 (Sheet 33 covers St. Bees to Keld; Sheet 34 covers Keld to Robin Hood’s Bay). However, if those are the only maps you have, you’ll find that they cover too narrow a corridor to provide information about alternate routes (and if you get lost, you might wander off the maps in short order). The 1:50,000 maps are listed in the available guidebooks.

- St. Bees, on the Irish Sea, is accessible by train. Robin Hood’s Bay on the North Sea is only a few miles from Whitby, a popular holiday spot, which is also accessible by train.

- Independent trekkers can do an unsupported hike in about 2 weeks. You can arrange to stay in B&Bs or inns virtually every day of the trip, although there’s one bit in the middle where you might have to arrange a support shuttle if you can’t manage a 20-mile day. Pack lunches, and expect to eat most breakfasts at your B&B and most dinners in pubs.

- Group trekking tours are available from a variety of outfitters.

- Pack-services are available so all you have to carry between inns is your personal gear. The best known is Packhorse, which offers a variety of hiker support services.